Turkey has disputed Greece's claims over the east Aegean islands, a move that threatens to reignite tensions between the two Mediterranean powers. A report by Al Jazeera notes that a renewed conflict between the two neighbours would add to the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation's (NATO) stress, as it is already trying to calm tensions between Russia and Ukraine.

As per letters sent to the United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres last July and September, Turkey, for the first time, disputed Greece’s authority over its east Aegean islands due to non-compliance with treaties. According to Turkey’s permanent representative, Feridun Sinirlioglu, the control over the Aegean islands was ceded to Greece on the specific condition that the islands be kept demilitarised, which Turkey asserts is no longer true.

Former Greek Foreign Minister Yiorgos Katrougalos told Al Jazeera, “The issue of demilitarisation of Aegean islands is being put forward for the first time as a precondition to go to The Hague. It is also being connected to sovereignty for the first time,” adding, “Turkey is piling on the issues in order to avoid talking about the real issue, which is maritime zones. Turkey has an irregular view of international law, and because it knows it’s in a minority of one… it spends its time exerting pressure through power moves.”

Greece occupied the islands of Limnos, Samothrace, Lesvos, Samos, Chios and Ikaria in the Balkan Wars of 1912-13 from the Ottoman Empire. The 1923 Treaty of Lausanne officially awarded sovereignty over the islands to Greece. However, the treaty forbids Athens from building naval bases, fortification or deploying troops on the islands. Likewise, the Treaty of 1914, drawn up in London, also conditioned the possession of the islands on their demilitarisation.

Before the 1960s, Athens had never built naval bases or deployed a large concentration of troops on the islands. But later, they did deploy forces after inter-communal relations broke down on Cyprus between Greek and Turkish Cypriots, further complicating relations between Athens and Ankara. In 1974, following a Greece-backed coup attempt on Cyprus, Turkey invaded the island. In response, Greece reinforced troops on its Aegean islands.

Defending Greece’s troop deployment on the Aegean islands, Konstantinos Filis, director of the Institute of Global Affairs at the American College of Greece, told Al Jazeera, “You have a revisionist neighbour who’s invaded every adjacent state. It’s sat in Cyprus for 48 years. It’s illegally invaded Syria and Iraq. I don’t think Turkey’s record suggests we can drop all concern that it can do the same [in the Aegean] if it thinks it can get away with it.”

Likewise, Lieutenant General Andreas Iliopoulos, former commander of the Supreme Military Command of the Interior and Islands (ASDEN), said Greece needs to worry since Turkey has formed units capable of invading the islands, adding that Greece needs to maintain enough security forces to deter a Turkish invasion.

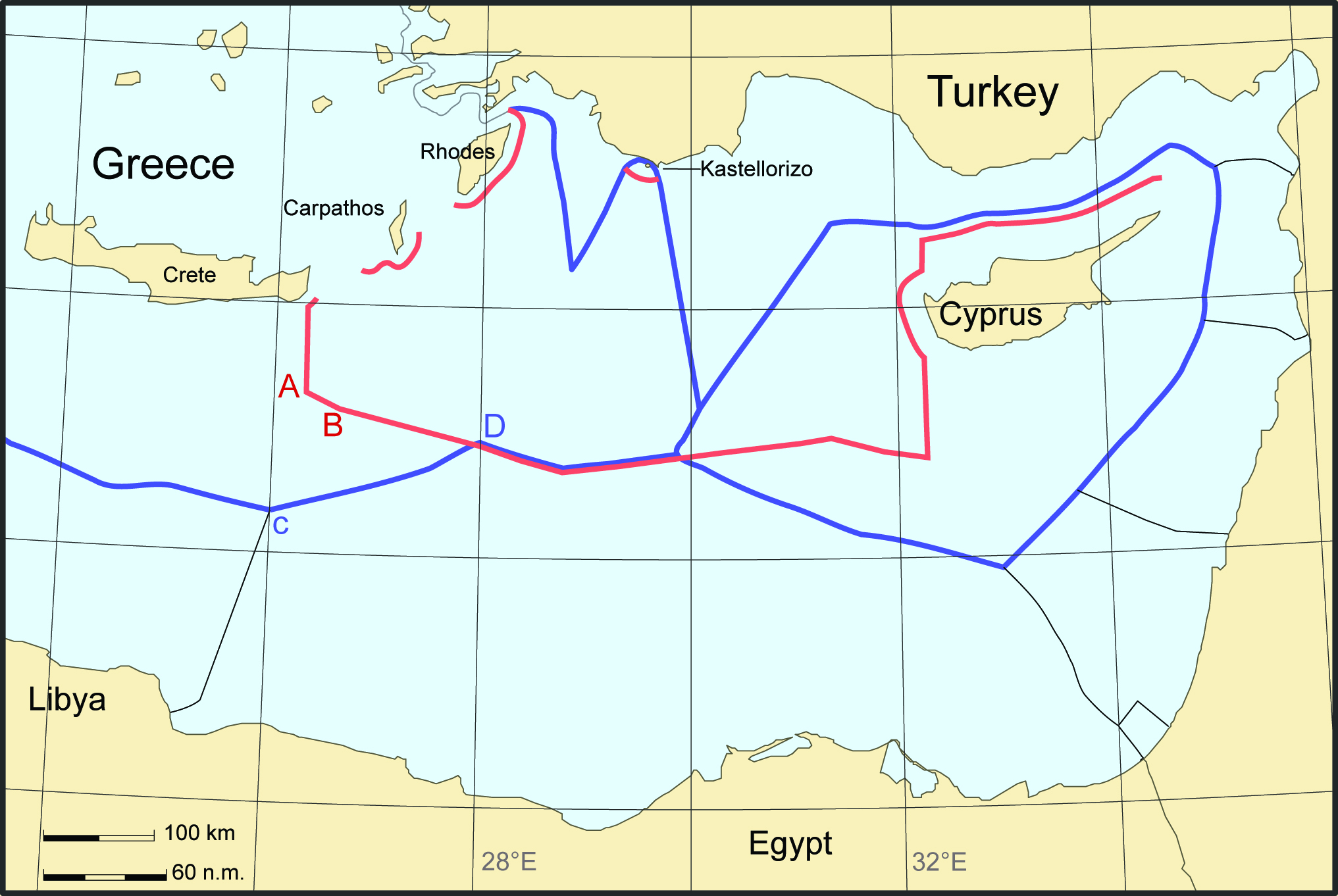

Reportedly, the dispute between Greece and Turkey is more about water than land. Both countries have six nautical miles (11 kilometres) of territorial water in the Aegean Sea. But according to the UN Convention on the International Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) 1982, the states can claim up to 12 miles (about 20 kilometres). Hence, the Convention gives Greece the possession of 71.5 per cent of the Aegean.

Citing the Convention, Greece said territorial water is the country’s sovereign right and not subject to negotiation with a third party.

In response, the Turkish ambassador to Athens Burak Özügergin said, “Any extension by Greece of its territorial waters beyond the present six [nautical] miles in the Aegean would have serious implications for Turkey. As such, any decision by Greece in that direction cannot be taken in a vacuum, as if Turkey does not exist.”

The rift between Greece and Turkey over territorial waters has been intensifying since 1973, with the Greek discovering oil fields and natural gas, therefore, making advances in hydrocarbon energy. During the same time, Turkey also promoted investments in hydrocarbon wealth by buying or building seismic survey ships and drill ships.

To settle the boundary dispute, Greece suggested arbitration at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) at The Hague. But Turkey has rejected the proposal, saying that the ICJ would upload UNCLOS and Turkey is not a signatory of the Convention. “Greece cannot, vis-à-vis Turkey, rely on its title under the [Lausanne Treaty] for the purposes of a maritime boundary delimitation,” Sinirlioglu said.