Another year has gone by, and what a year it was. Words perhaps cannot do justice to how turbulent and radically transformative 2020 was. Yet, while some aspects of our world have undergone paradigmatic shifts, others have remained untouched. One of these constants has of course been Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s enduring aversion to press conferences, which borders on willful negligence and apathy.

Press conferences offer an invaluable layer of transparency and accessibility to democratic societies, wherein the populace tacitly entrusts journalists to hold leaders accountable or at the very least gain answers to questions that the people themselves cannot directly ask. They provide a unique chance to challenge leaders to justify and clarify their decision-making outside of the ostensibly impenetrable walls of bureaucracy. At the same time, press conferences also extend an opportunity to leaders to venture outside of their echo chambers. Admittedly, parliamentary debates do allow for such introspection, but the hyper-polarity that characterises these debates often results in even well-made points being dismissed out of hand simply because they were made by the opposition, with the merits of their arguments completely ignored.

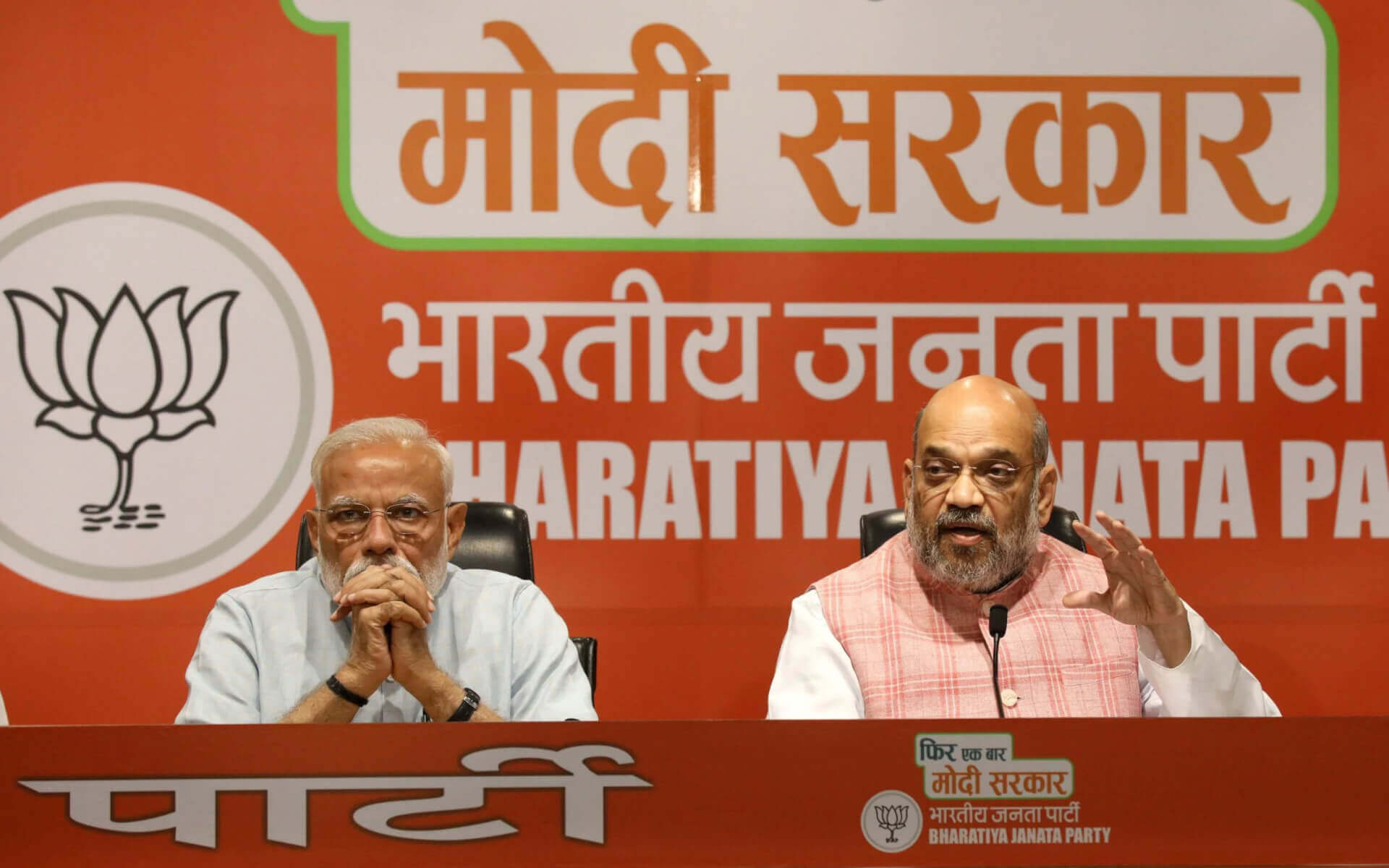

Yet, since entering office in 2014, PM Modi has participated in just one press conference. I use the word ‘participated’ quite generously, given that he didn’t answer a single question, instead deferring to the erstwhile party president Amit Shah, who has since taken up a role as the Minister of Home Affairs.

In fact, in January 2020, India Today reported that it had filed a Right to Information (RTI) request with the Prime Minister’s Office (PMO), asking for the number of press conferences delivered by the PM so far, along with the details of their dates and locations. However, the PMO said that it does not have this information “available on record”.

It must be conceded that Modi has given his fair share of interviews, particularly in the lead up to the general election in 2019, when he took part in ten print media and four television interviews over a 20-day period. However, upon closer inspection of these interviews, most of which have been republished on the PM’s website, it is clear that they were highly sanitised, choreographed, and scripted exercises that completely removed any possibility for candidness.

For all the failures and scandals under Modi’s predecessor, Dr. Manmohan Singh, the former leader was far more accessible to the press, despite the fact that Modi has sarcastically called him Maun (silence) Mohan Singh. In fact, in his book, ‘Changing India’, Singh wrote, “People say I was a silent prime minister. [...] I wasn’t the PM who was afraid of talking to the press. I met press regularly and on every foreign trip I undertook, I had a press conference on return.”

To be fair, Manmohan Singh might be seen as an exception to the rule, given that, between 1994 and 2004, none of India’s PMs—H.D. Deve Gowda, I.K. Gujral, and Atal Bihari Vajpayee—held any press conferences, indicating that this reluctance to speak to the media was perhaps set in motion far before Modi. However, this ignores the fact that, prior to 1994, Indian leaders typically addressed the press at least once a year.

Yet, even if one conveniently overlooks the fact that heads of state often recuse themselves from press duty in the face of intense public scrutiny (Rajiv Gandhi after the Bofors scandal, Bill Clinton after Monicagate, and George W. Bush after the Iraq invasion, to name but a few examples), this still doesn’t excuse the fact Modi has not conducted a single legitimate press conference, even after over 2,400 days in office. Moreover, his only unscripted interview as PM was with Bollywood superstar Akshay Kumar and had more to do with the pair’s love for mangoes than anything substantive.

While Modi and his supporters might argue that he does indeed engage with the population through his Mann Ki Baat radio show, which has aired over 70 episodes over the course of his two terms, this show only enables him to talk at citizens, not with them. Another counterpoint likely to be raised is that Modi has delegated press responsibilities to his Cabinet ministers—such as Minister of Health and Family Welfare Harsh Vardhan, Minister of Finance Nirmala Sitharaman, Minister of Defence Rajnath Singh, and Minister of External Affairs Subrahmanyam Jaishankar—to answer questions on his behalf. However, this draws a clear division between the leader of the country and the public, and thus infringes on commonly held democratic principles of accessibility and transparency.

That this trend has continued even in the face of a pandemic that has afflicted at least 10.3 million Indians and killed close to 150,000 is highly troublesome. In fact, India continues to record upwards of around 20,000 new cases every day, demonstrating the unprecedented need for leaders to participate in regular press conferences. Although Modi has delivered several national addresses, these do not allow for questioning. Not only has this gravely impeded the press, and thus the citizenry, from questioning the decisions that led to this ballooning crisis and the policies the government has undertaken to stymie the spread of the virus, it is also severely out of step with what other leaders of democratic nations have done during these uncertain and chaotic times.

United Kingdom (UK) PM Boris Johnson, Canadian PM Justin Trudeau, and New Zealand PM Jacinda Ardern, for instance, have all regularly delivered national addresses that have been accompanied by press questions that elucidated greater detail and clarification. Even Donald Trump—for all his bluster and his racist and xenophobic remarks, unfounded scientific claims, and attacks on the press—has conducted frequent press conferences in which reporters have gotten to question and even criticise his administration’s approach. The fact that Modi has not kept pace with his peers reflects poorly on India and undermines its legitimacy and credibility as a democracy. At the same time, it also undercuts its efforts to position itself as a global leader, given that it is not even meeting the minimum standards and expectations of good governance.

The fact that Modi has never participated in a press conference is hardly surprising in a country that ranks among the five deadliest nations for journalists and where press freedoms have taken a colossal downturn over the past few years. India now ranks 142nd out of 180 countries in the Reporters Without Borders’ 2020 World Press Freedom Index, down from 133rd in 2016.

India’s leader shuns questioning at every turn, yet the population has alarmingly been conditioned to accept this new troubling paradigm as a normal feature of a healthy democratic society. By refusing to hold a single press conference for over six years now, Modi has effectively co-opted the Indian citizenry into a system where his words are taken at face value and his lack of transparency and accessibility are mistaken for strength and assertiveness. In fact, a Pew research study in 2017 found that 55% of Indian favour a system “in which a strong leader can make decisions without interference from parliament or the courts”. Coupled with the fact that 85% of Indians ‘trust’ their government, the prevalence or surge in these beliefs has precipitated a situation in which Modi has essentially been given a free pass to remove pillar after pillar of the checks and balances in place to hold him accountable to the public. This sets a dangerous precedent for future Indian leaders, who will no doubt have reason to ask why they should be asked to uphold a standard their predecessor did not, all of which serves to chip away at the increasingly brittle building blocks of Indian democracy.

PM Modi Has Held Just One Press Conference in Six Years. What Does This Mean for India?

After over six years in office, and even amidst a global pandemic, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has still not answered a single question at a press conference.

January 2, 2021

IMAGE SOURCE: REXIndian PM Narendra Modi (L) held his first and only press conference in May 2019, but didn’t answer a single question, instead deferring to erstwhile BJP President Amit Shah.