Ethiopia just pulled out of a proposed round of talks with Egypt and Sudan that were set to be held in Washington later this week. The dialogue, which was convened to discuss the latest developments in the long-disputed Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) project on the Nile River, was to be mediated by the chief of the World Bank. But after years of failed trilateral negotiations, can the parties really rely on international law and arbitration to find a solution?

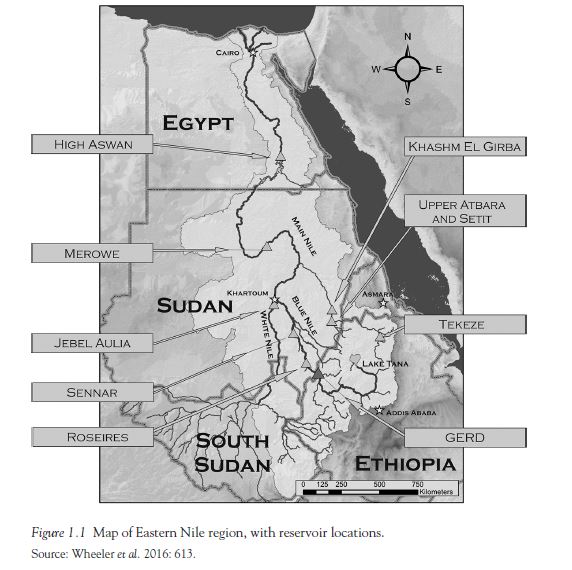

The Nile is the world’s longest river, passing through eleven riparian countries–Uganda, Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, Eritrea, South Sudan, Sudan, Ethiopia, and Egypt. Its main tributaries are the White Nile and the Blue Nile, which originate from Lake Victoria (bordering Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania) and Lake Tana (Ethiopia), respectively. The White and Blue Nile meet in Sudan’s Khartoum, and eventually flow as the Nile into Egypt.

The length of the river and its tributaries make the Nile an international watercourse, but it has historically been most closely associated with Egypt. It provides nearly 96% of Egypt’s renewable freshwater and has therefore become an important symbol of Egyptian culture and identity. Since the country receives abysmally low levels of rainfall, almost 95% of the country’s total population lives within 12 miles of the river, using its resources for agriculture, industrial production, and sewage treatment.

But over the past few decades, demands from other riparian states to access the river’s waters and utilize its resources have been perceived as a major national security threat by Egypt. The main issue remains to be that of the GERD, a $4.2 billion project with the aim of creating a massive hydroelectric power plant that would provide water and power to millions of Ethiopians, who currently face severe deprivation of these resources.

The Blue Nile in fact originates in Ethiopia's highlands, and provides the river with 85% of its total water flow. Put simply, it provides an overwhelming majority of the water that Egypt’s existence depends on. However, Ethiopia has not been allowed to access Egypt's water resources due to a myriad of political, economic and geostrategic reasons, even though it contributes such an overwhelming majority of Egypt's total available water resources.

The GERD has the potential to offer regional socioeconomic benefits by providing an improved and more efficient water management system, thereby also addressing certain challenges posed by climate change. It also provides opportunities beyond water, such as the integration of trade and markets, especially in the energy sectors. But its main challenge has been realizing a regional consensus on whether the project is actually beneficial to all parties and has thus been unable to reach an agreement for its most appropriate political and legal arrangements.

Egypt and Ethiopia have starkly competing views when it comes to the use of the Nile. Egypt sees itself as the first and natural user of the Nile, exploiting its water more than any other state. Its position on the GERD stems from fears that the dam will reduce its own supply of Nile water and that its diversion would lead to a significant amount of evaporation and water loss. Therefore, its paramount interest is preserving the current status quo. But Ethiopia, which only consumes less than 1% of the river’s water right now, stands to significantly reduce drought and malnourishment by exercising its right to utilize the natural resources in its own territory by way of the GERD.

Both countries have their own interpretations of how international law can serve their interests, especially with regards to the 1997 UN Convention on the Law of Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses (hereafter, the Convention). While unratified by both countries, this treaty is generally considered to be the most reliable representation of customary international law of watercourses. Many experts have referred to it to try and find an equitable solution to the issue, but its clauses are open to interpretation by either side.

From an Egyptian perspective, the 1902 Anglo-Ethiopian Treaty on the Nile and the Tana Dam nullifies any Ethiopian claim to the Nile, precluding the country from building the GERD. Further, Article 7 of the Convention says that states have a duty to take measures that will prevent significant harms to riparian states sharing international watercourses. Egypt argues that the GERD threatens to reduce its water resources and negatively impact the river’s water volume for all other states too. Concurrently, Egypt has also called upon the 1959 Nile Waters Agreement with Sudan, which adopts a view that simply rejects attempted claims by other riparian states on the Nile’s water resources. The 1959 Agreement was a modification of a 1929 treaty signed between Anglo-Egyptian Sudan and a nominally independent Egypt, under the supervision of the British, which recognized Sudan’s right to use the Nile’s water, but only in such a quantity that does not infringe the natural and historical rights of Egypt to the river waters.

But the validity of the 1902 treaty can be contested on the grounds of rebus sic stantibus, or 'things just standing', a legal doctrine that allows for treaties to become inapplicable after a significant change in circumstances. In this case, this can be used to examine whether Egypt is obligated to inherit an international treaty signed by its colonizers. Ethiopia can also nullify its own obligations to this treaty since it never formally ratified it. It is also questionable whether the 1929 and 1959 treaties are applicable to Ethiopia, given that they were signed bilaterally between Sudan and Egypt with no other parties. Additionally, the Harmon Doctrine relies on the idea that a sovereign territory has absolute and exclusive rights over the natural resources in its territory, and tied in with Article 5 of the Convention, which allows riparian states to share watercourses in a reasonable and equitable manner, this provides a solid case for Ethiopia to justify the GERD as being consistent with international law.

However, in an international system that lacks a central enforcement body, it is unclear whether Egypt would respect judgments made by international courts or arbitration bodies on an issue that they claim is inherently linked to its national security and economic interests. Additionally, given Egypt's geopolitical power over the Nile, it is unlikely that Ethiopia, which has already begun construction of the GERD, can continue to develop the project further. Egypt has long controlled the use of the Nile, despite the fact that upper riparian states have been requesting more access to its waters due to their environmental and economic vulnerabilities. The Cooperative Framework Agreement, signed by 5 riparian states as part of the Nile Basin Initiative, has also been rejected by both Egypt and Sudan.

It is also improbable that other countries will be willing to impose sanctions and pressure Egypt into reaching an equitable solution to the dispute, considering the country’s importance to international trade of natural gas and agricultural products. Egypt has strong trade partnerships with powers like the United States, United Kingdom, United Arab Emirates, and India, who are highly likely to refrain from interfering in this issue.

Hence, while arbitrated discussions may come across as an important step towards solving this issue, they are actually a bleak effort since the political power dynamics in the region are so skewed in one party’s favour. In this context, it is understandable why Ethiopia has requested for more time to consult its experts before signing a final deal in Washington. Upper riparian states have been contentiously surviving under these conditions so far, but the onus is on Egypt, and partly on Sudan, to guarantee that the region does not crumble under Egyptian hegemony. Cairo needs to acknowledge the scarcity of water in Ethiopia as an urgent issue that will persist until it is equitably resolved.

In addition to trying to resolve the dispute using international law, tangible solutions like the desalinization of seawater and increasing imports of ‘virtual water’ should be presented to Egypt as alternatives to its heavy dependence on the Nile. At the same time, there must be meaningful and non-partisan investigations into the actual environmental costs of the GERD project, with appropriate suggestions and changes made to its construction that can ensure that the geography of the watercourse does not suffer. While these are expensive and time-consuming options, the financial costs pale in comparison to the human and natural resources that will be lost in case this conflict escalates to full-blown war.

Reference List

Abebe, D. (2014). Egypt, Ethiopia, and the Nile: The Economics of International Water Law. Chicago Journal Of International Law, 15(1).

Abseno, M. (2013). Role and relevance of the 1997 UN Watercourses Convention in resolving transboundary water disputes in the Nile. International Journal Of River Basin Management, 11(2), 193-203. doi: 10.1080/15715124.2013.811415

Swain, A. (1997). Ethiopia, the Sudan, and Egypt: The Nile River Dispute. The Journal Of Modern African Studies, 35(4), 675-694. doi: 10.1017/s0022278x97002577

Yihdego, Z., Rieu-Clarke, A., & Cascão, A. (2018). The Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam and the Nile Basin. New York: Routledge.

Image Source: CNN